Leon's Furniture (TSE: $LNF)

Dominant Furniture Business Unlocking Value Through a Real Estate Spin-off

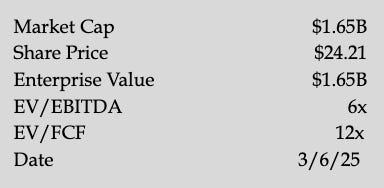

Key Ratios and Statistics ($CAD)

Company Overview

Leon’s is a 110-year-old furniture retailer, now the largest in Canada, holding the #1 position in furniture, #1 in appliances, and the #2 position in mattress sales. It has 83 stores under the Leon’s banner and 220 under The Brick banner. In addition to selling physical goods online and in-store, Leon’s offers installation and repair services, warranties, and credit insurance for their own furniture and furniture sold outside of their network. Since 1909, Ablan Leon and his sons grew the business to over $2.5B in annual revenue, retaining a majority stake after taking it public in 1969. The family continued to be very involved, holding a majority of executive positions and board seats, until they brought in their first outside CEO in 2021, Mike Walsh. Currently, the entire family is estimated to own about 60% of the total business, though this stake is divided between multiple family members and held in different trusts.

Business Lines

Leon’s organizes its business into three pillars. Retail plus (96% of revenue), financial services (4% of revenue), and real estate. In the financial services pillar, they operate through their Trans Global Insurance (TGI) subsidiary, which offers insurance and warranty services for customers who wish to be protected from hardship due to unforeseen events. 40% of Leon’s customers already purchase warranties, but Leon’s believes they have a significant opportunity to expand their addressable market for financial services through partner relationships, leveraging their scale to offer superior services. They currently earn roughly half of their revenue from outside of their own network but foresee this growing over time. The 3rd pillar was just recently added to convey their focus on unlocking the hidden value of the 5.6m square feet of real estate they own across the nation. In May of 2023, Leon’s announced a two-part strategy to create and spin off a REIT while developing a major property they plan on retaining. The REIT will be a standalone entity, operated by its own management team, and will work to develop and grow the portfolio, diversifying its tenant base beyond Leon’s.

The retail plus pillar can be divided into six main segments: retail stores, digital, distribution, after-sales service, wholesale, and commercial. Through its digital business, Leon’s generates $251m of annual e-commerce sales (10% of furniture sales) with 69m+ site visits per annum. The distribution segment is comprised of Leon’s standalone distribution centers, 22 delivery warehouse centers, and a last-mile delivery network, which is one of the largest networks in the nation. 30% of Leon’s last mile deliveries are third-party, which they plan on growing over time. Its after-sales installation and repair services offering is based on its network of service technicians, which is the largest in Canada. Leons’ technicians are also authorized to service appliances and electronics from more than 40 manufacturers and have said they intend to grow the business they carry out for manufacturers and vendors who otherwise lack the scale to service the Canadian market. Currently, ~50% of service revenue is generated from 3rd party channels. Under the wholesale segment, Leon’s operates a subsidiary that works with 55+ overseas manufacturers, custom designing private-label product lines. In the commercial segment, Leon’s sells goods directly to other businesses, including builders and commercial establishments. This is a faster-growing segment within the business, currently only generating $320m of annual sales.

Business History

Leon’s furniture began as the A. Leon Company, a small dry goods store on King Street in Welland, Ontario, was founded by a poor but industrious Lebanese immigrant named Ablan Leon. Ablan and his wife Lina went on to raise 11 children, who all grew up within the business and took part in running the store. Over its 110-year history, Leon’s became a true Canadian success story, expanding. When Ablan died in 1942, his son Lewie took over as President and CEO, whose vision and energy fueled Leon’s rapid expansion across Ontario and eventually all of Canada. Lewie was succeeded by his brother, Tom Leon, who effectively introduced “big-box” retailing to Canada in 1973, a model to which many other retailers owe their success. Tom also created Leon’s franchise division in 1980, which allowed the business to grow faster and use less capital in the process. Location count and sales continued to grow steadily until 2013, which is when Leon’s decided to make a huge $700m acquisition of The Brick (founded in 1971), their largest competitor, which was substantially bigger than them. This friendly acquisition gave the combined enormous scale overnight and made them Canada’s largest furniture trailer. They took on a total of $500m of debt (4.5 turns), and after the acquisition, the combined entity began to de-lever rapidly, using most of its free cash flow for debt paydown while steadily growing its dividend. During the 10-year post-acquisition period between 2013 and 2023, Leon’s only opened 3 new stores while growing same-store sales at 3.6% per year on average. Net income also grew at 7.3%, and EPS grew at 8.8% over this same period, while buybacks totaled $410m, dividends totaled $500m, and debt paydown totaled $445m. As soon as the debt was paid off in 2018, Leon’s began allocating more capital towards repurchasing shares, increasing the amount year over year. In just 3 years, between 2020 and 2023, Leon’s shrunk its share count by 14%, taking advantage of the post-pandemic increase in furniture sales. Specifically, in 2023, they bought back $244m of shares at a 20-30% lower share price than the business currently trades at, taking out a $135m term loan to do so. In 2023, a majority of their free cash flow was used to repay this term loan. Now, the business has effectively zero net debt, pays 40% of its earnings out as a dividend, and can begin regular share buybacks.

Throughout its public history, the Leon family has been recognized by shareholders for being good stewards of capital and excellent operators. They have acted like true owners of the business and treated shareholder capital as such. Acquiring The Brick was ultimately an incredible decision on their part as it was per-share accretive from day one and successfully integrated into Leon’s business as planned. The business has remained very consistent throughout its history without recording a single net loss in 30 years – as far as the financials go back – and remaining strong through the financial crisis. Leon’s also navigated the COVID period very well and certainly better than most of its competitors, avoiding excess/mismatched inventory issues and leveraging its buying power to acquire inventory amidst supply chain disruptions.

Many family members, starting with Ablan Leon and his 11 children, have passed through the business in various roles, with grandson, Terry Leon, most recently serving as long-time President and CEO (2005-2021). Prior to that, Terry was CFO and VP since 1989 and general counsel between 1984 and 1989. The Leon family has also implemented a fair compensation structure with regular base salaries and no egregious stock-based compensation. However, one area where they have historically fallen short is investor communication. Although some of these problems still exist, Leon's tries to maintain the secrecy of some of its operations, such as after-sales service, warranties, and distribution. However, recently, the company has started becoming more communicative after hiring Mike Walsh. More recently, it began providing quarterly investor presentations starting in 2024.

Capital allocation-wise, the company does not plan on opening new stores but rather shifting capex towards building a larger DC footprint, adding incremental square footage to existing DCs, or opening new ones altogether. Management is not agnostic towards taking on more debt, however, they do not plan to do so and have stated plans to continue increasing their dividend over time or adding special dividends as they see fit. They also do not foresee any more acquisitions, especially not at the scale they did in 2013, with The Brick citing limited opportunities, however, they remain open to the idea of smaller acquisitions. Rather, management is much more optimistic about organic growth in the fragmented industry they operate in, citing the large amounts of independents and regional businesses they still compete with on a day-to-day basis. Specifically, they said that being less than 20% of the market while still being the number one furniture retailer in the nation means they can continue to grow nicely.

Industry Overview

Canadian furniture retailing is a $25.3B industry known to be highly competitive, with low barriers to entry, which makes it very tough to succeed in. The business itself has very low operating margins, where ROIC is driven by how fast a retailer can turn its inventory. The main drivers of the industry, whether in Canada or internationally, are housing starts, per capita disposable income, and consumer confidence. In 2022 and 2023, the industry was hurt as elevated inflation and interest rate hikes pushed long-term borrowing costs, which discouraged real estate investments and weakened furniture sales. These losses, however, were insufficient to reverse the 2020 gains. 2024 industry revenue reflects a 3.6% CAGR since 2011 and a 1% CAGR since 2019, while in 2025, the industry is expected to grow at 5.2% to reach a completely normalized mid-cycle level. More recently, retailers have benefited from the ongoing macroeconomic recovery as the Bank of Canada began to lower interest rates in 2024, inflationary pressures cooled down, and improving disposable income supported rising demand for new furniture. Despite the fact that industry volume moves with the business cycle, furniture stores haven’t been too cyclical over the long term. Recently, financing options and BNPL have also become much more popular, further offsetting this. Mom-and-pop stores also get affected by the business cycle more than big box stores, as consumers find it harder to purchase furniture costing multiple thousands.

Canada has recently had the most aggressive immigration policy and fastest population growth of all G7 countries. The country welcomed 1.8 million people to the country over the past 5 years, which represented 5% of the 2019 population. This has caused a short supply of housing. The government aims to drive up the number of housing starts in the next few years, having listed housing affordability and availability as their #1 priority for the nation, calling for home construction “at a scale and pace not seen since the Second World War." Budget 2024, along with previously announced initiatives is aimed at supporting the construction of 2 million net homes over and above the 1.9 million homes expected to be built by 2031. A major benefactor of this dynamic will be the furniture business, as housing starts help to drive demand, where the industry is set to grow at ~3.7% CAGR over the next 5 years.

The industry is also reasonably fragmented and has been consolidating over the last decade. The number of retailers has declined due to weak large players like Sears, Eaton, and Zellers going out of business, while mom-and-pop operations face challenges with economies of scale. Covid was an especially bad time for these mom-and-pop operations who couldn't get access to inventory, which caused market share to shift towards those with scale. In the future, mom-and-pop will continue to be hurt disproportionately. Today, the majority of furniture manufacturers/brands have lost a lot of market power as the product has become more commoditized over time with outsourced manufacturing, constantly changing consumer tastes, and little to no marketing presence. Despite some product differentiation, retailers are mostly brand agnostic and view most product lines as fungible, able to be swapped out for something better at any point in time. As a result, these retailers now hold a lot more power than their suppliers, controlling access to the market and end consumers. Gross margins for the largest furniture retailers in the U.S. and Canada are very standard. Between 40-45% for most players, including higher-end players like Williams Sonoma and IKEA or Leon’s on the medium cost end. This allows the most scaled players to enjoy the highest operating margins, as they can acquire products for cheaper using their buying power.

Online Furniture Retail

The subsegment of online furniture retail within the industry is an even tougher business, given the challenges of trying to ship and transport bulky and damage-prone products right to a customer's doorstep. Returns are also almost impossible to handle, and oftentimes pure-play online retailers are stuck between having to refund orders or lose a customer entirely. As you can imagine, this ends up being very expensive and in its current state, not so economic. Another issue is that most people, even younger generations, still want to see products and try them firsthand, given that furniture is a very high-ticket item. As a result, driving e-commerce penetration in this industry is difficult. It has mostly begun on the low-cost end, with players like Wayfair, Amazon, and Overstock experiencing limited success. These players will find it more difficult to higher cost subsegments given that the higher ticket prices mean customers are more apprehensive towards buying furniture online, while breakages become more expensive to deal with

Specifically, the two largest independent online-only furniture retailers, Wayfair and Overstock remain unprofitable, although the former is getting closer to breaking even. Wayfair has significantly lower gross margins (~30%) than its brick-and-mortar counterparts, while its products are priced similarly for end customers and are arguably of worse quality. Overstock has many problems of its own, with many unhappy customers, more problems with breakages, lower quality products, and lower gross margins (23%). The two have historically used a drop-ship model where they held no inventory. Although more capital-light, this model is structurally unprofitable when it comes to selling furniture. Having realized this, Wayfair began spending heavily to build or rent physical distribution centers where they could hold inventory closer to their customers in hopes that their model would become more economic. Overstock has also been moving in this direction but is in a much worse position than Wayfair. This is effectively a huge strategic pivot, which can either save both of these businesses or hurt their shareholders even more. Overall, the online-only furniture retail model is largely unproven, and its viability remains to be seen long term. This kind of model is much more suited for smaller items and home accessories rather than larger pieces of furniture. Now that the one-time benefit from the pandemic is gone, online furniture retail has become a smaller but still growing part of the ecosystem. Long-term, many forecast that it will either die out in its current form as online-only players invest in physical locations or remain a smaller proportion of the industry than originally thought.

On the other hand, for brick-and-mortar players like Leon’s or Ikea, who already have large distribution footprints, offering online sales is much more straightforward and cheaper. They can much more easily ship products from their stores or warehouses, offer in-store pickup, and easily handle returns, allowing them to avoid the nightmares of online furniture retail. These two, in particular, have shown the ability to offer online sales profitably in Canada, and over time, scaled brick-and-mortar players like these will be able to gain significant market share if the proportion of e-commerce sales in the industry grows, as purely online retailers like Wayfair fight an uphill distribution battle and mom and pop or regional players don’t have the scale or resources to compete. Amazon is in its own league where it is an online retailer with the distribution and physical assets to compete at scale, however, furniture is not its bread and butter. It is still constrained by issues with returns but over time, it may be able to perform better in furniture retail than someone like Wayfair, whose business is still 50% dropshipping. Interestingly, Australia’s largest online-only furniture retailer, Temple and Webster, has recently ramped up its capex to build in-person showrooms for its products, understanding the desire for consumers to see and test out a wide selection of products. I think it reflects the direction of online furniture retail as a whole, where physical locations in high-foot traffic areas, either as stores or showrooms, are key to success.

Competitive Position

Furniture stores mainly compete based on price, quality, product selection, brand recognition, and shopping experience. Leon has approximately 12% market share in the Canadian furniture retail market, followed by Ikea at 11.3%. Outside of these two, no other players have a significant market share. Leon’s also makes up 8-9% of the total furniture stores in Canada, making it the largest by store count. They operate more on the medium-cost end between low-cost options like Amazon or Walmart or higher-cost options like Williams Sonoma or Restoration Hardware. While some items may be priced higher, particularly for premium collections, Leon's also features a selection of more affordable furniture that also caters to budget-conscious shoppers. Going up the cost curve, it becomes increasingly about brand identity and marketing rather than volume and scale, not to say these aspects still aren’t very important. In the medium cost range, Leon’s can play the volume and scale game better than anyone else while still maintaining a strong brand identity and a good level of customer loyalty. The difference between Leon’s and The Brick banners is that Leon’s tends to have slightly higher prices with better quality furniture, whereas The Brick has lower-cost furniture, larger discount and clearance sections, and a price match guarantee for competing products. If a customer at The Brick wants higher quality items, sales staff will refer them to Leon’s, and if a customer at Leon’s wants a cheaper product, sales staff will refer them to The Brick.

The difference between Leon’s as a whole and Ikea is that Ikea tends to fall lower on the cost spectrum, emphasizing contemporary design and selling a larger proportion of home accessories like textiles, lighting, kitchenware, and smaller furniture. Leon’s offers a mix of mid-range furniture, appliances, and electronics in a variety of styles that cater to different tastes, including traditional and contemporary options, with pricing between $500 and $3000.

To give you an idea of pricing, a regular 3-seat sofa costs $350 at Ikea with no delivery, assembly, and little financing options. They charge an additional $70 for shipping and assembly, however, a vast majority of Ikea customers do not choose this option. At The Brick, the cheapest, standard 3-seat sofa costs $452, with $0-50 delivery depending on the item, is already assembled, and has readily available financing. At Leon’s the cheapest 3-seat sofa costs $537, comes already assembled, is delivered and placed inside your home for free, and also has a lot of financing options.

In terms of shopping experience, the two are also quite different. Ikea’s stores are huge (300-500k square feet), 6-10x the size of Leon’s, which are already very big themselves (~50k square feet on average). Ikea entered Canada with its first store in 1976 but has not grown its overall location count significantly in two decades while continuing to make each existing store bigger and bigger. Effectively, their model is based on displays, where customers can see a variety of room designs, choose which furniture they want, pick it right up from the warehouse, take it home, and then assemble it themselves. Leon's offers a more traditional retail experience with knowledgeable staff available to assist customers in-store, placing a huge emphasis on customer service. The items they sell tend to be larger on average, and they have much more sales staff per square foot than Ikea. Leon’s employees are adamant that the quality of their products is much better than Ikea’s, while pricing is still good. The main difference is Leon’s offers free in-home delivery and assembly for all of its products, unlike Ikea. At The Brick, customers may have to pay for this option for certain products. But both also emphasize financing, insurance, and warranties. Finally, brand positioning is also quite different for the two. Ikea is seen as a global leader in affordable home furnishings with an emphasis on contemporary design and sustainability. Leon’s and The Brick are seen as trusted Canadian brands with a long history of serving their customers with a more personalized shopping experience for its customers.

Due to the difference in business model, Ikea and Leon’s + The Brick tend to have slightly different customer demographics too. Ikea was built on low-cost, assemble-yourself furniture, but if you want delivery and assembly it ends up being more expensive. A study found that the peak age for IKEA customers is 24 years old, and it's most popular with people in their late 20s and early 30s. It's best fit for people looking for products that are not heirloom quality but good enough for a first, temporary, apartment, or house. However, after the age of 34, some people’s love for cheap, diy furniture seems to drop off. Customers of Leon’s and the Brick tend to be more middle-aged (30+), with couples shopping together and senior citizens too. These customers are looking for more permanent, premium, and longer-lasting pieces to put in their longer-term homes or apartments. Rather than picking it up themselves and assembling it, they likely value the free delivery and assembly service that Leon’s offers as well as the after-sales service options through its technician network.

The customer mindset of someone shopping for furniture at Amazon, Costco, or Walmart is also very different. Their quality tends to be worse, and they can’t match the breadth and depth of a pure-play brick-and-mortar furniture retailer. It’s more of a fast furniture approach, which differs from traditional furniture retail.

Mom-and-pop stores tend to be slightly different too. They usually serve the same customer base over time, and it’s a much more relationship-based business. Their main value proposition for customers is customizability, where they pride themselves on working with the customers to find them their perfect piece, whereas the big box stores may have more “cookie-cutter” options and less variety. What mom-and-pop stores lack is low-cost items. They are usually much more expensive than their big-box counterparts. To illustrate, the average price of a large furniture item at a mom-and-pop store is around $2000, whereas at The Brick or Leon’s it's more like $800. Their customer base also tends to be older people in better financial positions, continuing to senior citizens buying their last-ever pieces of furniture. These customers are usually less time-sensitive, meaning they are willing to wait for longer to get the exact piece they want. On the other hand, the majority of customers at a big box retailer expect the furniture faster, which means distribution and inventory become differentiating factors.

Scale Economies

Competition within the furniture retail industry is based on dominating local markets. Significant local scale is required to succeed in the business. The bigger players have turned to building national scale as a way to both expand beyond local markets and reinvest a lot of capital back into their businesses. This gives them certain advantages over players with solely local scale, offsetting a bit of the geographic dilution that comes with reinvesting more capital into growing their businesses and having to spend more on distribution. However, at its core, the best way to run a furniture business has historically been to avoid geographic dilution, utilize local buying power, and grow location count sparingly.

Leon’s is currently one of the largest importers of shipping containers into Canada (10,000+ every year), providing them with massive purchasing cost advantages when compared to their competition. It is estimated that they pay around 66% less for the cost of a standard 40 ft. shipping container while maintaining standard markups on the furniture, enabling them to post gross margins significantly in excess of mom-and-pop operations, and on par with some of the best-run retailers in the US. They also have relationships with over 500 suppliers on the ground presence in Asia, through a design team. These advantages were demonstrated during the pandemic when Leon’s scale and purchasing power made them one of the only furniture retailers who could readily obtain available products in line with their pre-covid purchasing. While weaker players were exposed during this time. Leon’s also has control over access to the furniture market for upcoming designers and manufacturers as they have the widest store network and largest customer base. They are seen as the defacto brand to introduce new products into the market. This also means these manufacturers may be eager to position their products inside a Leon’s at a cheaper price. A recent partnership with mattress-in-a-box company Resident is a great example of Leon’s using their owned distribution and store footprint to allow Resident to connect with their customers. This also means that Resident’s marketing spend is directly bringing customers into Leon’s stores at zero cost to the company.

Leon’s also demonstrates its scale by having one of the largest last-mile delivery fleets and the largest network of service technicians in the nation. This allows them to deliver and service furniture that they themselves didn’t sell, acting as a distribution or service partner for other furniture stores. Their national scale also allows them to have higher market share in the commercial furniture segment, which is 7% of industry revenue but over 10% of Leon’s revenue, selling directly to builders and businesses. They also consistently rank in the top ten TV advertisers in the country, often surpassing Tim Hortons and even McDonald’s in certain geographies, while still having a normal operating margin for the industry.

Some furniture companies also employ a model where they sell inventory, as it is just leaving the port in its country of manufacture – likely Southeast Asia. Basically, they take forward orders and by the time the container arrives they may have sold a significant proportion of the inventory inside, allowing them to hold less inventory and cover the price of their products before they are even received. On Leon’s balance sheet, this shows up as customer deposits and decreases once the furniture is delivered to the end customer. However, this does not work if a customer needs the item quickly, where the retailer must give them a product as soon as they can. Leon’s can also use its buying power to delay payment to their suppliers, which means their scale also helps it be a more cash-flow generative business, using less working capital. In effect, they can sell inventory and collect cash as soon as the shipment leaves their suppliers' local port while delaying their payment even after they receive that furniture in Canada.

However, all things considered, Leon’s has actually become a worse business over time, which many other retailers that have pursued geographic expansion have experienced. ROIC declined from 20% to 10% in the last 24 years, meaning that geographic expansion essentially diluted the benefits of expanding nationally. This is likely because as store density decreased, logistics costs increased, with new DCs having to be built in order to effectively transport bulky and expensive furniture across Leon’s network. Since 2015, ROIC has slowly increased and stabilized after Leon’s stopped growing its location count and instead let some benefits of their national scale develop like their warranty, service, commercial, and distribution, with operating margins expanding from 6 to 7.5% on average.

This is mainly a result of Leon’s capital allocation policies, considering that it is a family business. The family probably did see that lower store density would decrease ROIC. However, they were happy to do so as long as incremental ROIC was still attractive relative to their cost of capital because they still needed a place to reinvest the free cash flow Leon produces. They likely didn’t weigh this against any other opportunities because they would not be able to allocate capital anywhere else and chose to just focus on the business that they knew very well. This is why Nebraska Furniture Mart under Berkshire Hathaway is run the exact opposite way, with just 4 locations being opened in 40 years, where reinvestment into the furniture business is weighed against an incredibly wide set of opportunities. In hindsight, it's easy to say they should not have grown the business as much as they did, but it probably made the most sense for the family. More recently, Leon’s has shifted to paying dividends and buying back its shares, which is favorable, while investing more heavily in distribution centers to offset the effect of geographic dilution. This allows them to more effectively transport furniture to each store, as it has to travel less distance from the nearest DC, which receives direct shipments from the port. With no intentions of growing location count, management understands that opening stores is likely not the best use of capital. Overall, I think ROIC will either remain at 10% or possibly increase slightly as they collect more revenue from 3rd parties in their other business lines, such as after-sales service and warranties, and invest in distribution, decreasing costs and boosting operating margins.

NFM Case Study

Buffett purchased 90% of Nebraska Furniture Mart in 1983, valuing the total business at $61 million. That year earnings before taxes were $3.8 million and earnings after taxes were $1.5 million, meaning Buffett paid a 16x pre-tax multiple or a 41x post-tax multiple. The business generated over $100m in annual revenue out of a single 200k square foot store in Omaha, representing $500 per square foot. No other furniture store in the country came close to that volume and that one NFM store sells more furniture and carpets than all Omaha furniture stores combined. In Bufett’s 1983 letter, he said, “One question I always ask myself in appraising a business is how I would like, assuming I had ample capital and skilled personnel, to compete with it. I’d rather wrestle grizzlies than compete with Mrs. B and her progeny. They buy brilliantly, they operate at expense ratios competitors don’t even dream about, and they then pass on to their customers much of the savings. It is the ideal business—one built upon exceptional value to the customer that in turn translates into exceptional economics for its owners.”

NFM operates using a scale economies shared model where they hold gross margins at 20-22%, half of what competitors in the industry target. Their closest competitor, Levitz, has a 44% gross margin. This allows them to drive volume and revenue, incur benefits to scale from purchasing, and pass all benefits to customers in the form of lower prices (holding gross margins constant again), which drives more volume, which creates more benefits, and so on. This is a very positive feedback loop helping them turn inventory faster and faster over time. NFM did the most volume of any single furniture store in the United States by far, and that too in Omaha, NE. They had exceptional efficiency where operating expenses (payroll, occupancy, advertising, etc.) were about 16.5% of sales versus 35.6% at Levitz. Buffett says that the cost savings that NFM delivers to customers allow it to “constantly widen its geographical reach and thus to enjoy growth well beyond the natural growth of the Omaha market.”

Overall, the key ingredients to success for NFM were unparalleled depth and breadth of merchandise at one location, the lowest operating costs in the business, the shrewdest of buying, gross margins and prices fall below competitors, and friendly, personalized service with family members on hand at all times. This was an ideal business model where both the business and the customer one, and the suppliers benefited from being able to sell huge volumes of furniture to NFM at one time. It was a family business, built on relationships and providing true value.

Ms. B was also an incredible operator, teaching her sons well too. She was an incredibly passionate person with an intense focus. She even left price tags on the furniture in her own home to remind her of her business. NFM was so dominant that its Omaha competitors even sued Ms. B for violating fair trade laws by having too low prices. She not only won all cases but received invaluable publicity and became a household name. At the end of one case, after demonstrating she could profitably sell carpet at a huge discount from the prevailing price, she sold the judge $1400 worth of carpet. She also received an honorary degree in Commercial Science from NYU.

Her three sons continued to run the business after her death. One of them, Louie, earned a reputation as the shrewdest furniture buyer in the country. Dillards, one of the most successful department store companies in the country has furniture sections in many of its stores and does very well in the business. Shortly before they opened their Omaha store, the chairman, William Dillard, announced this new location would not sell furniture. He said, “we don’t want to compete with NFM, we think they are the best there is”.

Starting with $100m in 1983, NFM compounded revenue at 7.7% under BRK’s ownership growing to now 5 stores with $1.6B of revenue at $550 sales per square foot. This was a high ROIC business with limited reinvestment opportunities, which was fine for Berkshire considering they had many other places to allocate capital at very high rates of return. The Leon family took the other route, scaling their business, allowing them to reinvest back into the business and grow at lower incremental returns on capital.

Situation set-up

Leon’s core furniture business is arguably undervalued, trading at just 13x earnings and 9x free cash flow. However, the more interesting situation is surrounding its real estate. It holds 5.6M sq ft of real estate, a mix of both retail and industrial space across the country, and has announced that it is looking to spin off 5.2m sq ft into a publicly traded REIT, following the example of two other large Canadian retailers, Loblaws, and Canadian Tire, which spun-off their REITs in 2018 and 2013 respectively. Both REITs currently trade at 5-6% cap rates. On top of this Leon’s owns 40 acres of land near downtown Toronto, which they plan on turning into 4,000 residential units, leaving some retail and mixed-use space too. The development of this land is more uncertain but potentially adds a lot of value to the business.

In 2021, following a 6-year stint with the business as a VP of Operations and COO, Leon’s promoted Mike Walsh to CEO, making him the first-ever non-family member CEO to occupy the position in Leon’s entire 100+ year history. Conveniently, Michael just so happens to be one of the people behind Canadian Tire’s REIT spin-off in 2013, having been their VP of Operations from 2012 to 2015. His public comments make it clear that he understands the value of Leon’s real estate and is exploring ways to unlock it.

Since his hiring, Mike has quickly demonstrated his skill as an operator and capital allocator, meaningfully adjusting Leon’s inventory assortment coming out of COVID, returning significant amounts of capital, and putting a plan together to unlock significant shareholder value. Mike was also behind the recent IR push, serving to highlight the strength of Leon’s business.

In 2022, the board also brought in Victor Diab as CFO, another non-family member, who was at Canadian Tire from 2012 to 2022 and most recently, occupied their VP of finance role.

In 2023, Leon’s reported a decline in revenue, with system-wide sales down 2.7% and revenue down 2.5%. However, growth actually resumed halfway through the year, with the declines only occurring in the first half. Leon’s decline was partly caused by a decline in consumer spending, but they also say it was due to a choice they made in the final months of 2022 to meaningfully reduce inventory. At that time, they said that freight costs were unusually high, the economy had slowed, and consumers were being more cautious in a higher rate environment. Leon’s wanted to avoid overcommitting to high-cost merchandise. In the second half of the year, Leon's inventory levels normalized, and the business returned back to growth. In the first 9 months of 2024, sales grew 3.1% year over year.

REIT

Leon’s has stated that it plans on taking the REIT public when it feels the market will maximize its value, with a target in mid to late 2025. This portfolio of 5.2m square feet of owned real estate is diversified across Canada, with Ontario representing 41% of the total square footage, Alberta 27%, and British Columbia and Quebec at approximately 9% each. 22% of this real estate is in The Greater Toronto Area This is the same strategy that was enacted by both Loblaw Companies and Canadian Tire, two of Canada’s largest big box retail businesses, who both spun off their portfolios of real estate in 2013. This where Diab and Walsh come in is significant as those two were a key part of Canadian Tire during the pre and post-REIT spin-off period.

While Leon’s plans on retaining a majority stake in the REIT, this will give them a sizable chunk of cash which can be used for buybacks or a special dividend, allowing the real estate to be publicly valued on its own. Although there will be a negative impact on earnings and cash flow due to increases in lease payments following the transaction, Leon’s will collect sizable distributions from the REIT, partially offsetting these lease payments. There’s also some undeveloped land that the REIT will own, and its management team may decide to follow other Canadian REITs in using this land to build condos or apartments amidst the housing shortage, the unlock value.

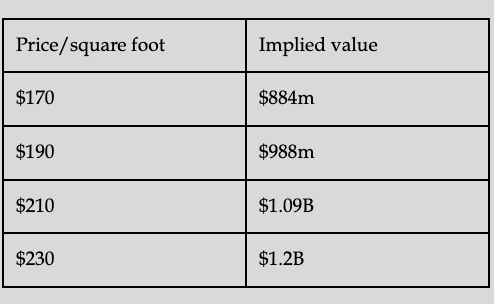

CBRE estimates rent per square foot nationally for similar assets retail assets to be $15-20. Using this estimate and a 6-8% cap rate, in line with what similar REITs trade at, would translate to $900m to $2B. However, considering that Leon’s is effectively a single-tenant REIT, I think the low end of that range is more reasonable, while $2B seems like an unlikely scenario. Another way to value the REIT would be by simply applying a price per square foot based on comparable REITs. Canadian retail REITs as a whole trade at around $250 per square foot. But considering that this REIT will basically be a single-tenant REIT, it will probably trade at some discount. For reference, almost all Canadian non-industrial REITs trade above $180/sq ft, so I think $170 is a very conservative starting point.

In 2023, Leon’s paid $93 million to rent 6.6 million square feet of space or ~$14 per square foot. CT REIT, the Canadian tire spin-off pays $19 per square foot in rent, which is a higher estimate given that their properties tend to be slightly newer and higher-end. This means that 5.2 million square feet of newly rented real estate will likely end up costing Leon’s $73 million to $100 million, with the most likely scenario being around $80m. Additionally, the property expenses will be transferred to the REIT, which for comparable REITs tends to be about 25% of revenue, which should save Leon’s $20m. Finally, Leon’s will receive distributions from the REIT, which will further offset the rent payment in proportion to the 80-90% stake they are likely to retain. These would be something like $40m, assuming the REIT pays 90% of its earnings out as dividends and has the same proportion of overhead expenses as CT REIT. Overall, it seems like Leon’s earnings post-REIT will decrease by around $20m, leaving the core business at a post-REIT multiple of 18x earnings. When using a 6-8% cap rate on the $60m of expected NOI for the REIT yields a value of $750-$1B

Development Property

In January 2024, Leon’s announced it had rezoned a 40-acre piece of land it owns in Toronto at the intersection of the 401 and the 400, the busiest section of highway in all of North America. The plan is to eventually have 4.6 million square feet of retail, including a new flagship Leon’s store, residential and commercial on the site. To pull this off, Leon’s plans to partner with developers, aiming for a total of 4,000 residential properties on the land, including residential, high-rise, low-rise, rental units, and townhouses. The land has already been converted from a general employment area to a regeneration area, and secondary approval to move forward with a development plan will likely be granted in 2025. Although the value of such a development is uncertain, similar-sized developments in the U.S. have been worth upwards of $1B. Some predict that Leon’s share of this value will be nearly $200-$400, in line with the proportion they expect it to give to developers. While a development like this could take 10-15 years even, Leon’s at any point in time could sell it entirely to one of their partner developers and pull these cash flows forwards.

Sleep Country Acquisition

The Sleep Country acquisition is also useful to take note considering it was one of Leon’s closest peers, and the acquirer involved has a reputation for being very fair and value-focused. In July of 2024, it was announced that Fairfax Financial Holdings would be acquiring Sleep Country, Canada’s largest pure-play mattress retailer, with 307 stores around the country, at an 18x earnings multiple. The total purchase price was $1.7B, which represented $35 per share. While Sleep Country isn’t a perfect comparison because of its narrow focus and smaller stores, Leon’s is Canada’s second-largest mattress seller. Sleep Country seems like a business of comparable quality too, with ROE and ROIC in the same range as Leon’s.

Fairfax has also been active in this industry in the past. In 2012, they owned 33% of The Brick before it was acquired by Leon’s. Their CEO at the time, Bill Gregson, did good things for the company, which caught the attention of Mark and Terry Leon, the fourth generation of the Leon’s family. In Bill’s public remarks to shareholders, he noted that the Leon’s family had built their business with great integrity, treated their people well, and ran a high-quality enterprise. Fairfax also played an active role in the deal, helping Leon’s buy The Brick by backstopping a convertible bond issue that was to be used to pay for $5.4 per share of The Brick. This was a friendly deal fully supported by the boards of both companies, with Fairfax voting in favor of the deal. The deal also used no investment bankers and instead was done completely through the internal teams of both companies.

Canadian Tire REIT

As mentioned throughout the write-up, the Canadian Tire REIT is probably indicative of how the Leon’s REIT will be structured. This REIT was spun off at a valuation of $200 per square foot with 18 million square feet but also had a slightly more diversified tenant basis and higher quality, newer properties. However, there were also some lower quality and less desirable properties mixed in and it was also done over 10 years ago, in a cheaper real estate market. Canadian Tire themselves retained an 85% interest in the REIT, selling the remaining 15% to the public through an IPO at a $3.5B total valuation. They used the proceeds to invest back into the business at their management team's discretion. Leon’s may choose to do the same and continue to invest in distribution or it may pay out a special dividend or buyback shares. It had a positive effect on Canadian Tire’s share price as expected, which went from $70 in 2012 to $100 in 2014. Over time they also issued shares in CT REIT and used the proceeds to pay out dividends, which was essentially a way for Canadian Tire to reduce its effective stake down to 66% by 2019. This seemed like their plan from the beginning as they talked about the REIT allowing them to access funds at an attractive cost of capital when the first proposed it. For reference, Loblaws started with a 62% stake in their REIT, Choice Properties, which is Canada’s largest REIT. Then in 2018, they sold their entire stake to Great-West Lifeco, a property and asset management company, to focus on their core grocery and pharmacy business.

Thesis

Leon’s Furniture is a slightly above-average quality business with a decent competitive advantage. It still faces a good amount of competition from many other furniture retailers, where price is the number one factor behind a consumer's choice.

Although it doesn’t have spectacular growth potential or incredibly high returns on capital, it is a very stable and consistent business that can weather macroeconomic headwinds, as shown by its consistent profitability for 30 straight years. As the Canadian furniture industry experiences growth from new housing starts driven by a short supply of homes and government incentives, Leon’s, which is the largest furniture company in Canada, is in an excellent position to benefit.

Occupying such a position in the industry gives Leon some benefits, as seen on its national scale, including its network of service technicians, distribution capabilities, last-mile delivery fleet, and warranty businesses. If e-commerce grows as a % of industry revenue, I expect Leon’s to gain incremental market share, taking business away from mom-and-pop stores or regional chains that cannot match its ability to handle returns, delivery, and at-home service, installation, and support. I also expect Leon’s to win long-term vs. online-only players, mainly Wayfair, who have severely underinvested in distribution and are in a much worse competitive position when it comes to selling and delivering furniture online.

12x forward free cash flow seems very reasonable for a business of this quality, which should be able to grow at 2-3% (with the economy) over the longer term, with a near-term tailwind from housing starts driving 3-4% growth over 5-7 years. If they do continue to take market share from mom and pops as management expects, this growth rate will be higher. However, along with a fair business at a below-average price, investors are also getting the upside of a potential REIT spin-off, which seems very likely to happen in 6 months to a year, and what I view as an option on the Toronto development property – uncertain but could be very valuable. Walsh should be able to complete the spin-off, having gone through the same process before, and if not, Leon can explore other options, such as a sale-leaseback. The REIT and the development alone could be worth upwards of 80% of the current market cap, with the spin-off potentially acting as a near-term catalyst to unlock value. All of this upside is essentially free, given that the core business looks undervalued by itself, while the downside seems very protected.

Valuation

The furniture business should roughly trade closer to 15-17x earnings, given that it seems like a fair quality business and should grow along with the economy. This produces a value of around $2-2.2B. However, if the REIT is created, Leon will be responsible for rent/lease payments to the REIT, while also receiving dividends back from the REIT in proportion to the majority stake they plan on keeping. Overall, this could reduce earnings by about 10-20% for the core business. Adjusting for that yields a value of around $1.5-1.8B. Based on a range of outcomes for the core business, REIT, and development, figure 11 shows what upside may look like. I think the most likely scenario is 40-50% upside, whereas 60% or more upside requires more aggressive assumptions for all three value drivers.

Risks

The furniture industry, including mattresses, appliances, and home electronics, is very competitive. A variety of stores sell these products such as department stores, specialty stores, regional chains, and independents. Thus, if competitive pressures intensify, Leon’s may be at risk of losing market share. Although I expect Leon’s to gain market share or at the least maintain its position, this is still a very real risk. There’s also the risk from general economic cycles, where a long, drawn-out, and deep recession would hurt Leon’s and the entire industry as consumer spending and housing starts to decline. The final main risk is the risk that e-commerce penetration increases substantially and for some reason, Leon’s can’t maintain its market share in online sales. I think this is a less likely risk given consumer behavior and purchasing patterns for furniture. In my view, the most likely scenario is that e-commerce penetration does increase over time, at a slow pace, considering that younger generations seem to be more open to online shopping for larger, higher-ticket items. However, along with this, I would not be surprised if Leon’s were able to take a greater share of e-commerce than they currently have in Brick and Mortar or at the very least maintain a proportional share in line with their current share. Their superior distribution capabilities, last-mile delivery fleet, wide store network, and service technician network should allow them to be a major winner in the industry long-ter,m but e-commerce may still pose a threat.